Theory in Practice — OODA, Mapping, Antifragility

Based on a talk presented at Velocity 2016 in Santa Clara, this post tries to show the practical application of concepts like OODA, Wardley Maps, and Antifragility with examples from my day-to-day work at a startup.

Theory

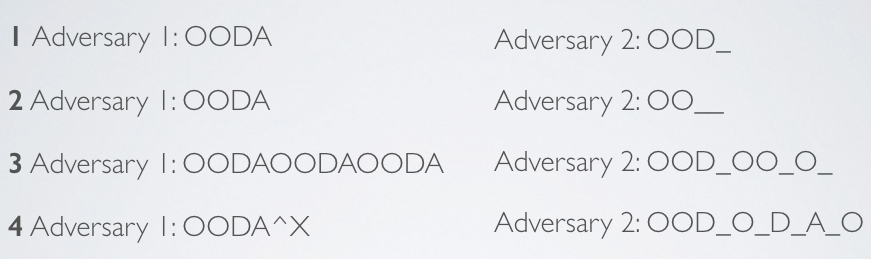

OODA — Observe Orient Decide Act

Observe the situation, i.e. acquire data. Orient to the data, the universe of discourse, the operating environment, what is and isn’t possible, and other actors and their actions. Decide on a course of action. Act on it.

Typically, you hear people saying that we’re supposed to go through the loop [O -> O -> D -> A -> O -> O…] faster than others. Let’s break that down.

- If we traverse the loop before an adversary acts, then whatever they are acting to achieve may not matter because we have changed the environment in some way that nullifies or dulls the effectiveness of their action. They are acting on a outdated model of the world.

- If we traverse the loop before they decides, we may short circuit their process and cause them to jump to the start because new data has come in suggesting the model is wrong.

- If we traverse the loop at this faster tempo continuously, we frustrate their attempt to orient — causing disorientation — changing the environment faster than they can apprehend, much rather act.

- We move further ahead in time. Or to be more exact, they’re falling further backwards: unable to match observations to models, change orientation, have confidence in decisions, or act meaningfully.

This is what Boyd called operating inside someone’s time scale.

Our main means of connecting the components of the loop is via models (and projections of cause/effect based on those models). Observations are tied into and given context via models.

Another way to think of models is as maps.

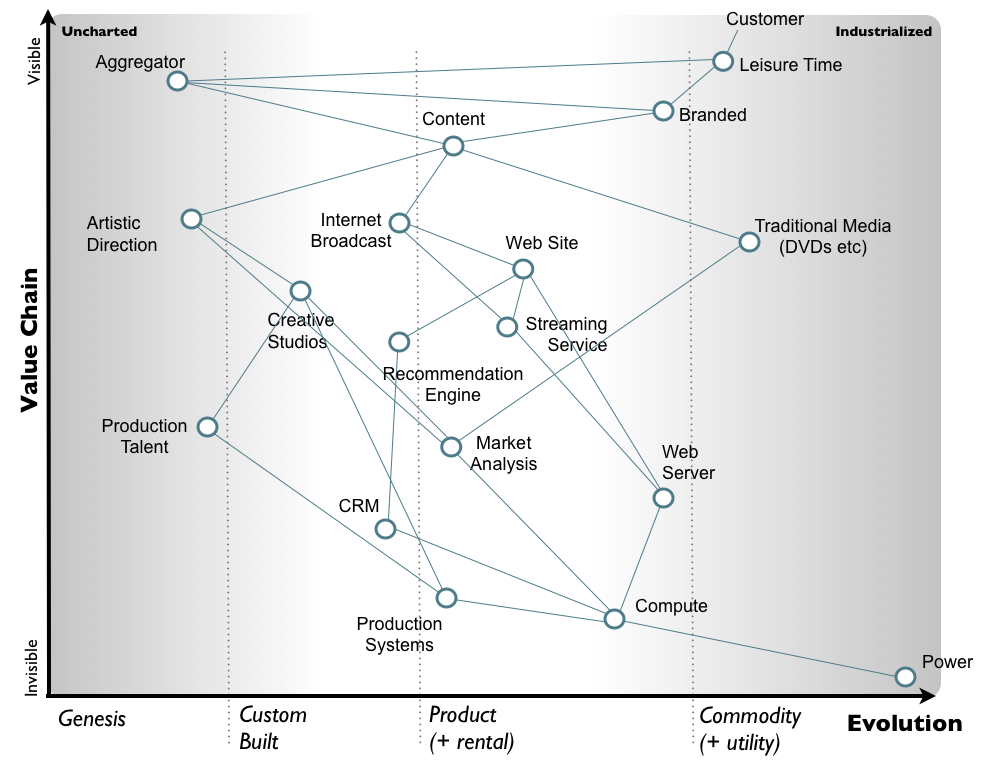

Mapping

This is a Wardley, or Value Chain, Map. It’s the most useful model I’ve encountered for building products or businesses. Watch Simon’s OSCONkeynotes or read his blog to really dig in to the concept.

It starts with a user need at the top. What problem are we solving? How are we going to make someone’s life better.

Then it goes deep, laying out the supply (dependency) chain of components needed to service that need. The further down, the less visible and exposed the component is to our end user. For example, if we’re building a SaaS product, users are never (or should never) be exposed to the systems running the code. This is the Y axis.

The X axis is where it gets interesting. It provides stages of development that components map into. Nearly everything naturally moves from the left to the right over time as invented or discovered things become standardized, well understood, built by more producers competing for market share, until some eventually become absolute commodities or provided as utilities. It’s a kind of natural evolution.

- Genesis [stage 1]: something that’s being discovered/built from scratch

- Custom Built [stage 2]: built out of existing technologies but highly customized for a specific use case and not generalized to broad use

- Product [stage 3]: COTS software, something bought from someone else vs self-built

- Commodity [stage 4]: something that’s effectively fungible, for which there are multiple equivalent providers, that may be provided as a utility

Individual components, regardless of their stage, can be expanded into finer grained production pipelines, marked as something that’s either provided or consumed, and aligned with methodologies like in-house-agile-developed vs outsourced-to-cloud-provider.

Finally, each component can be treaded as a piece on the field and moving them around as functions of product strategy, attempts at changing the competitive landscape.

For example, open sourcing something to try to commoditize it or create a de facto standard. Or providing something as a utility / platform / API in order to build a moat (that you can also consume) out of the ecosystem that you engender around it

[Anti]Fragility

But everything is constantly changing. Which means our map can become stale fast. Which makes us fragile — exposed and unaware — to ever more risks. Black swans.

A black swan is only a black swan if you can’t predict it (or assign it a probability). They’re inevitable. As our maps become out of synch with the real world, non-black swans become black swans. It’s possible to be fragile to one kind of black swan but not another. There are activities or patterns that will make us fragile with respect to something. And those that will make us antifragile.

There’s no such thing as absolute antifragility. It’s contextual. A severe enough stressor over a short enough time period will destroy anything.

Maps can be made robust (to some scale) through adaptive mechanisms, learning and correcting to match for change in the world.

But beyond some scale, every map is fragile. The world can change faster than, or so severely that, any attempt to update the map fails. Events can get inside a map’s timescale.

Systems can be antifragile (to some scale) through constant stress, breakage, refactoring, rebuilding, adaptation and evolution. This is basically how Netflix’s chaos army + the system-evolution mechanism that is their army of brains iterating on the construction and operation of their systems works.

For example, here’s our model of the APIs or services we rely on — smooth and reliable, with clearly defined boundaries and expected behavior. This is also the model that those things have of the APIs and services they rely on. All the way down

But this is how most things actually look. Eventually in the course of operation, the gaps line up in such a way that a minor fault event becomes magnified into systemic failure.

Systems, software, teams, societies — everything eventually crumbles under the weight of it’s own technical debt.

Which is why we should be refactoring, paying down technical debt, or what I just call “doing maintenance”, all the time at every layer.

Practice

Caveats: My views don’t represent those of my employer or anyone else and a great deal of detail is left out.

Example: mapping at work

I’ll build a map for a new feature SignalFx just released in beta.

Starting with the user need which I describe as “discovering known and unknown unknowns.”

A lot is left out, but generally speaking: on the top left we have the need, immediately connected to that is how that need is served and proceeding out from there is a generalized view of the supply chain of components needed to make it so.

Some things worth noting:

- We rely on utility or commodity technology and services for all our infrastructure hardware and software, like operating systems, and also middleware — using things like AWS, Linux, Kafka, Cassandra, Elasticsearch, etc. This is standard behavior for a software as a service company.

- We rely on relatively standard means of getting data into the system, in our case collectd, StatsD, Dropwizard metrics, etc., and a host of plugins and libraries that conform to open APIs and use well known open, or public, protocols.

- We can see that there’s a lynchpin without which the map would fall apart, the streaming real-time analytics engine.

- In order to build what was needed to serve that user need we started with, we needed to build many other things: a specialized quantization service, lossless + real-time message bus, specialized timeseries database, a high-performance metadata store, real-time streaming analytics engine, and an interactive real-time web-based visualization for streaming data, etc.

Many of the components we built are, if they were generalized, standalone products that others build entire companies on. In this specific case those are all the open source technologies — Kafka, Cassandra, Elasticsearch, etc — that we built our highly customized components out of.

Given all of that, I have one important positive question each day: Given the amount of time I’m going to spend working today, what one thing can I do to move the needle in serving this user need through what we do?

And one negative one, seeking invalidation: Is there any evidence that our map, our hypothesis, our approach, have been invalidated?

- Is our projected user need real? Will people pay for it? Is it the problem they actually want solved? Do people really not want leverage? Do they not want to be given more power and time through tools? Do they want thinking to be replaced, instead of force-multiplied?

- Is our lynchpin really the point of leverage and differentiation we believe it to be? Has it become a commodity and we’re just fooling ourselves into thinking we’ve built something novel?

- Has the territory changed in any way, through macro trends or the actions of players in the ecosystem, such that we need to rework our model?

Example: knowing what’s possible

Imagine we want to build a personal relationship management [PRM] system to meet some a need for people to manage their complicated and ever-growing network of contacts.

The top left is where we’re starting from. The y-axis is basically features or sub-capabilities that add up to something. The x-axis is what they add up to: products or capabilities that are in and of themselves valuable. The bar for something belonging in the leading row is being a viable sub-product. Everything in the column below are the features needed for it. Where the line is for being able to declare that we’ve built a minimum usable product may be different per column, as may the line for what constitutes an MVP.

We have limited time, people, and money. So we can only build so many things at once. Let’s say we can only build one column at a time. We have to get to usability and viability in each column to be able to expand users and business sufficiently to build the next column.

But every single thing we build limits our options for the next thing we build. We can go down and we can go to the right.

We can scrap everything further below and further to the right of the point we’re at today and figure out something else to build from where we are. This is effectively a pivot.

But what we can’t do is go from 3 steps down in the 2nd column [a graph of your contacts that’s auto generated based on your communications with them over Gmail, Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, and Outlook email that shows degrees of separation] to, say, a restaurant reservations and point of sales SaaS product. There’s no getting from here to there. But you can get from here to a product referral network.

Seeking invalidation:

- Is a personal relationship management service still the best way to serve the user need? Is there a better way?

- Can we build to that better way from where we are?

- Have we built an minimum usable product? Is it viable? Can we generate enough business (or funding) from what we’ve built to build the next thing?

Example: hiring for antifragility

The core principle of antifragility, as I see it, is to arrange things such that we get stronger through stress. More or less how muscle growth works.

How do you build that into an organization? How do you decrease brittleness? The only way I’ve ever found is through diversity. Inclusion, and forced exposure, to different points of views is absolutely necessary if we don’t want to get stuck — stuck in a way of thinking, stuck in a way of dealing with issues, stuck with a pattern of response, stuck in a point of view that makes us blind to threats and opportunities.

Think of it this way. We have to stir the pot in order to not get trapped in a local maximum. Not once, but constantly. Even a hint of homogeneity — whether it’s of people or ideas or practices or anything — is a clear signal that we are fragilizing and becoming brittle.

For my team, here’s what that looks like: no one in my org has a background in tech except for me. My background is both deep and wide, but it’s 90% tech. There’re just a large swath of things I’m blind to. What I’ve got is people who’ve studied art, biology, english lit, who don’t look like me or think like me. Things that I’m fragile to, they’re not. As a group, we’re way stronger than if I was hiring copies of myself.

Seeking invalidation:

- Is this the right team? Can they do what we need to do right now? Can they do what we need to do in a quarter, in a year, in 5 years?

- Are they the wrong team, or am I failing at

- Helping them get from where they are to where I need them to be?

- Getting the most out of their perspectives?

- Creating a safe environment for them to bring their best to the table?

Questions

John Allspaw asked if it’s possible for a person to be anti fragile. I don’t think so. I don’t think any given person or component of a system can be antifragile. I think groups and systems can be made antifragile. Complexity can be a symptom of the build up of antifragility in a system. Beyond some envelope, it’s also a harbinger of collapse.

Peter van Hardenberg asked where I set the bar. Assuming baseline functional competence (can do the job at hand), the next thing I look for is differentness. What do you bring to the table that’s unique from what we already have?

Wrapping up, here are the daily operating principles arising from this study:

Always be refactoring

Diversity has intrinsic value

Territory > Map

Seek invalidation

The above builds on ideas in these previous talks and posts:

The original abstract was way too ambitious for a 40 min time slot. The presentation suffered quite a bit from me erratically moving through the material, trying to pack in too many ideas.